When A Customer is Grateful to Be Your Customer

by Robert W. Palmatier, PhD

"Relationship Marketing" (RM) refers to a long-term and mutually beneficial arrangement in which both the buyer and seller focus on value enhancement with the goal of providing a more satisfying exchange. RM encompasses all activities directed toward establishing, developing, and maintaining successful relationships (Morgan and Hunt 1994). When you think about RM, two concepts come to mind: trust and commitment. But, what other mechanisms make RM effective at improving seller performance? A key goal of selling is to build and sustain customer relationships (DeWulf, Odekerken-Schroder, and Iacobucci 2001). For real estate agents, the longevity of the relationship is paramount. Not only do you want your customers to buy/sell every house through you, their referrals are priceless. In this article, we discuss the role of customer gratitude in establishing effective buyer and seller relationships. Our research suggests it is important for a seller to go beyond providing the obvious benefit of a new home to creating more positive buyer perceptions of a seller's motive.

Role of Gratitude in RM

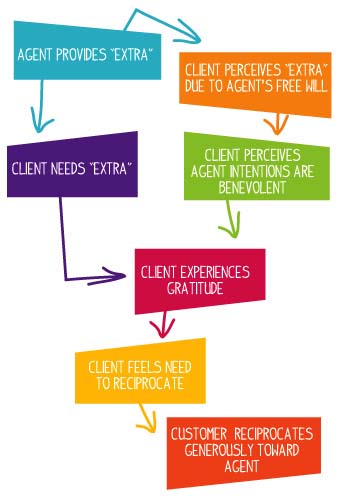

Gratitude, the emotional appreciation for benefits received, accompanied by a desire to reciprocate is an important concept for understanding RM effectiveness (Morales 2005). Examples of relationship marketing investments in real estate would include an agent providing extra effort for a buyer or seller in adapting policies, providing small favors, or considerations (e.g. meals, gifts, personalized notes). These relationship marketing investments generate customer feelings of gratitude, which lead to gratitude-based reciprocal behaviors, resulting in enhanced seller performance. After receiving a benefit, people feel a deep-rooted psychological pressure to reciprocate, such that the act of reciprocating can generate pleasure, whereas the failure to repay obligations can lead to guilt (Dahl, Honea, and Manchanda 2005). The extensive role of gratitude in how people perceive, feel about, and repay benefits gained in the seller/buyer exchange process makes gratitude a prime candidate for explaining how RM affects performance beyond the influence of trust and commitment. For residential real estate, consider that seller investment in RM generates feelings of gratitude, which have a strong influence on buyers' short-term purchase intentions. Gratitude is a fundamental social component of human interactions that provides an emotional foundation for  reciprocal behaviors. You scratch my back, and I feel obligated to scratch yours. Researchers have identified two key aspects of gratitude: affective and behavioral. Feelings of gratitude generate a built-in psychological pressure to return the favor. Thus, we define the affective aspect of gratitude, or feelings of gratitude, as feelings of gratefulness, thankfulness, or appreciation for a benefit received. We define the behavioral aspect, or gratitude-based reciprocal behaviors, as actions to repay or reciprocate benefits received in response to feelings of gratefulness (Morales 2005). The RM cycle could "pay off" for the seller in a single episode, but in ongoing relationships such as in real estate, multiple episodes of RM lead to feelings of gratitude which in turn lead to the accumulation of gratitude-based behaviors and lasting improvement in the seller's performance. Before this experience of gratitude can be perceived, the client needs to understand that other people are intentional beings whose actions are motivated by desire and belief (McAdams and Bauer 2004). To feel gratitude, the client must recognize that the agent's benevolence is intentional and, also, attribute good intentions to the agent (Gouldner 1960). Prior research has shown that consumers satisfy their sense of obligation and feelings of gratitude by changing their purchase behavior (Morales 2005). As your clients become aware of receiving some RM benefit (e.g. extra effort, small courtesy, gift) they should feel grateful and be more likely to buy from you during this encounter, recognizing that this benefit may not exist for them in the future (McCullough, Tsang, and Emmons 2004). Gratitude-based reciprocal behaviors may consist of the client buying other product/services from the agent (higher share of wallet), reducing pressure on the agent to lower prices, or giving agents opportunities to be introduced to friends or associates who may also be in the market to buy/sell a home. Gratitude does not act independently of trust and commitment. Because feelings affect judgments, people often decide whether they can initially trust someone by examining the feelings they have toward that person (Jones and George 1998). Algoe, Haidt, and Gable (2008) find that gratitude for benefits received increases a receiver's perceptions of the giver, including emotional responses (e.g., liking, closeness, how well the giver "understands" the recipient). Unselfish behavior provides a basis for trust, including when people express genuine care and concern for the welfare of others (McAllister 1995), such as through the delivery of a valuable benefit. According to recent research, gratitude has a significant, positive effect on one person's evaluation of another's trustworthiness, which results in higher levels of trust (Dunn and Schweitzer 2005). In addition, Young (2006) argues that gratitude is a relationship-sustaining emotion, with an important impact on maintaining trust in a relationship. Because buyers and sellers participate in many cycles of reciprocation, buyers receive important evidence of seller behaviors, which increases their confidence in the seller's future actions (Doney and Cannon 1997).

reciprocal behaviors. You scratch my back, and I feel obligated to scratch yours. Researchers have identified two key aspects of gratitude: affective and behavioral. Feelings of gratitude generate a built-in psychological pressure to return the favor. Thus, we define the affective aspect of gratitude, or feelings of gratitude, as feelings of gratefulness, thankfulness, or appreciation for a benefit received. We define the behavioral aspect, or gratitude-based reciprocal behaviors, as actions to repay or reciprocate benefits received in response to feelings of gratefulness (Morales 2005). The RM cycle could "pay off" for the seller in a single episode, but in ongoing relationships such as in real estate, multiple episodes of RM lead to feelings of gratitude which in turn lead to the accumulation of gratitude-based behaviors and lasting improvement in the seller's performance. Before this experience of gratitude can be perceived, the client needs to understand that other people are intentional beings whose actions are motivated by desire and belief (McAdams and Bauer 2004). To feel gratitude, the client must recognize that the agent's benevolence is intentional and, also, attribute good intentions to the agent (Gouldner 1960). Prior research has shown that consumers satisfy their sense of obligation and feelings of gratitude by changing their purchase behavior (Morales 2005). As your clients become aware of receiving some RM benefit (e.g. extra effort, small courtesy, gift) they should feel grateful and be more likely to buy from you during this encounter, recognizing that this benefit may not exist for them in the future (McCullough, Tsang, and Emmons 2004). Gratitude-based reciprocal behaviors may consist of the client buying other product/services from the agent (higher share of wallet), reducing pressure on the agent to lower prices, or giving agents opportunities to be introduced to friends or associates who may also be in the market to buy/sell a home. Gratitude does not act independently of trust and commitment. Because feelings affect judgments, people often decide whether they can initially trust someone by examining the feelings they have toward that person (Jones and George 1998). Algoe, Haidt, and Gable (2008) find that gratitude for benefits received increases a receiver's perceptions of the giver, including emotional responses (e.g., liking, closeness, how well the giver "understands" the recipient). Unselfish behavior provides a basis for trust, including when people express genuine care and concern for the welfare of others (McAllister 1995), such as through the delivery of a valuable benefit. According to recent research, gratitude has a significant, positive effect on one person's evaluation of another's trustworthiness, which results in higher levels of trust (Dunn and Schweitzer 2005). In addition, Young (2006) argues that gratitude is a relationship-sustaining emotion, with an important impact on maintaining trust in a relationship. Because buyers and sellers participate in many cycles of reciprocation, buyers receive important evidence of seller behaviors, which increases their confidence in the seller's future actions (Doney and Cannon 1997).

Client Perceptions

Four factors need to be taken into consideration: client perceptions of 1) the amount of free will the agent has in making the investment, 2) the agent's motives in making the investment, and 3) the amount of risk the agent takes in making the investment, as well as 4) the client's need for the benefits received. The return on RM investments may be highly sensitive to clients' perception of the agent's free will in providing the benefit. For example, if an agent dedicates a certain percent of his/her commission to market a property for a client, the client will be more appreciative than if it is stated in the contract that the agent has chosen to do so (the action appears to be an addendum or optional). Thus, when clients perceive RM investments as an act of free will, they feel more grateful than when they perceive the actions as duty-based obligations or contractual requirements (Gouldner 1960; Malhotra and Murnighan 2002). The second factor pertains to the client's perception of the agent's motive. A motive represents a desire or need that incites an action, and people often ponder others' motives for action. For example, when a child comes home and randomly complements his mother on her beauty, the mother probably responds by asking, "How much do you need?" or "What did you do?" Clients' inferences about motives play key roles in their perceptions of marketers' actions (Campbell and Kirmani 2000), such that they may experience gratitude when they perceive favors as coming from agents with benevolent intentions rather than underlying ulterior motives such as competition with other agents or simply increasing commissions (Gouldner 1960). The third factor is the perception of the amount of risk the agent undertakes in providing the relationship investment. As the client perceives higher levels of agent risk in making the RM investment, he or she should feel more obligated and grateful toward the seller. Consider the situation in which a job candidate from out of town asks a real estate agent to provide a day-long tour of homes in the area, under the assumption that the job candidate will buy a home there if he or she takes the job. The agent is taking a risk in investing time in that potential buyer because the buyer may not get or take the job offer and thus will never move to that city. The prospective buyer should recognize the risk the relationship investment demands of the real estate agent and thus feels grateful. In turn, if the prospective buyer accepts a job in the area, he or she is more likely to use that agent's assistance in purchasing a home, or, perhaps, to recommend the agent to others who might be moving there. Fourth, the client's perceived need for the received benefit should affect his or her gratitude. Appreciating something (e.g., event, person, behavior) involves noticing and acknowledging its value or meaning and feeling a positive emotional connection to it. Most people are grateful for a gift, especially when that gift contains value, though the perceived value of and gratitude for a gift increase when the gift represents a needed item. Our research shows the positive impact of RM investments on commitment and commitment's positive impact on purchase intentions. In addition, feelings of gratitude seem to be an important mediating mechanism that helps drive RM outcomes. We also find that increasing clients' perceptions of agent free will and benevolent motives, as well as increasing client need, significantly increase clients' feelings of gratitude. Our research shows that gratitude-based reciprocal behaviors can drive company performance outcomes, specifically, sales revenue and sales growth.  Gratitude emerges as a key element that influences relationships. Gratitude represents an "imperative force" that causes people to reciprocate the benefits they receive (Komter 2004). In addition to its mediating role, gratitude increases a client's trust in the agent, both strengthening the quality of the relationship and positively affecting agent outcomes. This finding is consistent with Young's (2006) argument that gratitude is a relationship-sustaining emotion that increases relational trust. Feelings of gratitude and reciprocity are important for motivating clients to build trust with and behave equitably toward their agent (Cialdini and Goldstein 2004). Agents should recognize the window of opportunity after an RM investment, during which they can "collect" on feelings of gratitude.

Gratitude emerges as a key element that influences relationships. Gratitude represents an "imperative force" that causes people to reciprocate the benefits they receive (Komter 2004). In addition to its mediating role, gratitude increases a client's trust in the agent, both strengthening the quality of the relationship and positively affecting agent outcomes. This finding is consistent with Young's (2006) argument that gratitude is a relationship-sustaining emotion that increases relational trust. Feelings of gratitude and reciprocity are important for motivating clients to build trust with and behave equitably toward their agent (Cialdini and Goldstein 2004). Agents should recognize the window of opportunity after an RM investment, during which they can "collect" on feelings of gratitude.

Strategies for RM Effectiveness

From our research three strategies emerge for increasing client feelings of gratitude and thus RM's effectiveness. First, agents should design programs that increase customers' perceptions of the agent's free will and benevolence when providing the benefit. Formalized "loyalty" programs with written rules or in which clients earn "points" toward a reward are not likely to generate significant gratitude or reciprocation because they lack the perception of free will. When necessary to solve a client's problem, you can personalize otherwise standardized rewards or provide small favors unique to the buyer. Likewise, letting the buyer know that the agent is working on commission would undermine perceptions of the benevolence of the motive for the RM investment. Companies should avoid benefits that appear to provide personal gain for the agent. In contrast, companies can leverage motive deliberately, positioning themselves as caring more for the client than for the commission the buyer generates by providing benefits that illustrate such benevolence. For example, a firm that offers to provide competitive rate comparisons sometimes shows that their firm is not the most desirable choice. Such efforts are much more likely to generate gratitude, reciprocation, and future purchase loyalty than efforts that seem to be designed only to increase sales or lock the buyer in to dealing with a specific firm. Second, an agent can best utilize RM investments by providing a benefit when the client's need is the highest and the benefit provides the most perceived value. Although the perceived cost of the program to the client should increase customer gratitude, so will the value provided by the benefit. For example, money spent by the agent marketing and promoting a property. While the client sees the cost as an expense to the agent, the increased money spent hopefully will help the property receive more offers and eventually sell for a higher price. Third, designing programs to generate high levels of gratitude is important, but returns will appear only if clients act on these feelings. Agents should give clients opportunities to reciprocate soon after providing them with an RM benefit, which takes advantage of high levels of gratitude, prevents guilt rationalization, and leads to cycles of reciprocation. For example, this would be a great time for the agent to ask for referrals from his/her clients. Our findings suggest the importance of establishing meaningful relationships with clients. Relationship Marketing (RM) recognizes the long-term value to an agent of keeping clients and developing their feelings of gratitude, trust and commitment. Rather than a continuous focus on the acquisition of new clients, perhaps the solution to achieving higher sales revenue and growth lies in a less numbers-driven approach. The solution may lie in utilizing buyer emotions and perceptions to provide a more holistic, personalized purchase, and using that purchase experience to create stronger agent/client ties.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

References

Algoe, Sara B., Jonathan Haidt, and Shelly L. Gable (2008), "Beyond Reciprocity: Gratitude and Relationships in Everyday Life," Emotion, 8 (3), 425-29. Campbell, Margaret C. and Amna Kirmani (2000), "Consumers' Use of Persuasion Knowledge: The Effects of Accessibility and Cognitive Capacity on Perceptions of an Influence Agent," Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (June), 69-83. Cialdini, Robert B. and Noah J. Goldstein (2004), "Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity," Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591-621. Dahl, Darren W., Heather Honea, and Rajesh V. Manchanda (2005), "Three Rs of Interpersonal Consumer Guilt: Relationship, Reciprocity, Reparation," Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15 (4), 307-315. De Wulf, Kristof, Gaby Odekerken-Schröder, and Dawn Iacobucci (2001), "Investments in Consumer Relationships: A Cross-Country and Cross-Industry Exploration," Journal of Marketing, 65 (October), 33-50. Doney, Patricia M. and Joseph P. Cannon (1997), "An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships," Journal of Marketing, 61 (April), 35-51. Dunn, Jennifer R. and Maurice E. Schweitzer (2005), "Feeling and Believing: The Influence of Emotion on Trust," Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 88 (May), 736-48. Gouldner, Alvin W. (1960), "The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement," American Sociology Review, 25 (April), 161-78. Jones, Gareth R. and Jennifer M. George (1998), "The Experience and Evolution of Trust: Implications for Cooperation and Teamwork," Academy of Management Review, 23 (July), 531-46. Komter, Aafke E. (2004), "Gratitude and Gift Exchange," in The Psychology of Gratitude, Robert A. Emmons and Michael E. McCullough, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 195-213. Malhotra, Deepak and J. Keith Murnighan (2002), "The Effects of Contracts on Interpersonal Trust," Administrative Science Quarterly, 47 (September), 534-59. McAllister, Daniel J. (1995), "Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations," Academy of Management Journal, 38 (February),24-59. McCullough, Michael E., Jo-Ann Tsang, and Robert A. Emmons (2004), "Gratitude in Intermediate Affective Terrain: Links of Grateful Moods to Individual Differences and Daily Emotional Experience," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86 (February), 295-309. Morales, Andrea C. (2005), "Giving Firms an 'E' for Effort: Consumer Responses to High-Effort Firms," Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (March), 806-812. Morgan, Robert M. and Shelby D. Hunt (1994), "The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 58 (July), 20-38. Young, Louise (2006), "Trust: Looking Forward and Back," Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21 (7), 439-45.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

About the Author

Robert W. Palmatier, PhD, Associate Professor of Marketing

John C. Narver Endowed Professor in Business Administration, University of Washington

Robert W. Palmatier holds a Bachelors and Masters in Electrical Engineering from Georgia Institute of Technology, an MBA from Georgia State University, and a PhD from the University of Missouri. He presently is the John C. Narver Chair of Business Administration at the University of Washington's Foster School of Business. Prior to academia, he held numerous positions in industry including President & Chief Operating Officer of C&K Components, European General Manager, and Sales & Marketing Manager at Tyco-Raychem Corporation. He has also served as a Lieutenant onboard nuclear submarines in the United States Navy. His research interest is focused on relationship marketing and business strategy. His research has appeared in Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Marketing Science, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Retailing, and the International Journal of Research in Marketing. His research has received the Harold H. Maynard award for significant contribution to marketing theory and thought in the Journal of Marketing. He teaches marketing strategy in both the EMBA and MBA programs.