Comparing Apples-to-Apples or Apples-to-Oranges: Choice Difficulty in Home Buying

Eunice Kim Cho, PhD, Uzma Khan, PhD, and Ravi Dhar, PhD

Consumers are faced with choices each day. Marketers try desperately to influence our decision-making process, capturing our attention and appealing to our instincts with pithy ads like Apple's "Think Different" or Burger King's "Have it Your Way." These types of advertisements often work well, helping consumers draw comparisons and make selections between similar products in a noisy marketplace.

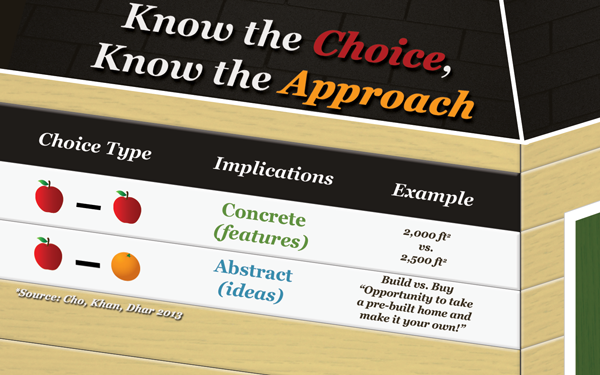

Of course, some choices are more difficult to navigate than others. As the number of available alternatives increase so does decision difficulty (e.g., Iyengar and Lepper 2000). Similarly, most consumers (and researchers) would agree that "apples-to-apples" comparisons are generally easier to navigate than "apples-to-oranges" comparisons (Bettman and Sujan 1987; Johnson 1984; Zhang and Markman 2001). Choosing between two competing brands of cars, for example, is assumed to be an easier choice to make than choosing between a new car and a trip to Europe.

In the real estate context, consider a choice between two single-family homes. Perhaps these homes differ on a number of features, including the number of bedrooms, size of yard, year of construction, and proximity to work. This apples-to-apples choice presents home options with features that can be readily compared. Such a choice is assumed to be relatively easier than choosing between an apples-to-oranges choice, or a choice with options that do not share features. An example of a choice with dissimilar features might include a choice between a single-family home (which might have a large back yard, four bedrooms, a quiet cul de sac), and a condo (which might have proximity to great restaurants, a pool, a 24-hour concierge, and a no-hassle cleaning and maintenance services). Another example of an apples-to-oranges choice might include a choice between buying or building a new home.

Can the Difficulty of a Choice Be Influenced, or Even Reversed?

Contrary to popular belief, our research shows that the ease or difficulty of making a choice is not inherent in the choices themselves; rather, choice difficulty has much to do with the state-of-mind of the chooser. We show that an apples-to-oranges choice can in fact be easier than an apples-to-apples choice depending on the decision-maker's state-of-mind. Decision makers in an abstract state-of-mind take a big picture perspective. They tend to focus on the holistic aspects of the decision and base their decisions on criteria related to the overall essence of the choice options. Decision makers in a concrete state-of-mind, however, tend to focus on the details of stimuli. Their decisions are based on specific feature-based criteria.

Based on the specific tendencies of different mindsets, we predicted that consumers in an abstract, big-picture state-of-mind would find apple-to-oranges comparisons easier than apples-to-apples comparisons, as big-picture criteria are more suitable for the former. The reverse should be true for consumers in a concrete, narrow state-of-mind, as specific attribute-based criteria are more suitable for apples-to-apples comparisons than for apples-to-oranges comparisons.

Chess Versus Cheese

To demonstrate this idea, in one study we asked participants to choose between two different chess sets, and asked others to choose between a chess set and a cheese platter. All other things being equal, choosing between a chess set and a cheese platter should be harder than choosing between two chess sets. Furthermore, we asked half of the participants in each choice-set condition to either make the decision for themselves or to choose for someone else. We know from previous research that thinking of another person puts people in an abstract, big-picture frame-of-mind, whereas thinking about oneself induces a more concrete and narrow mindset. This shift happens because distance from another person makes us less likely to get entangled in distracting details and forces us to address the heart of the issue.

The results of our experiment were illuminating. When choosing for themselves, participants rated the chess-versus-chess choice easier than the cheese-versus-chess decision. But an opposite pattern of results emerged when participants chose for a mere acquaintance. That is, once they were forced to think in abstract, big-picture terms (i.e., about someone else), the cheese-versus-chess decision became easier than the chess-versus-chess choice.

Our research reveals that when choosing for others, people tend to use big-picture, more holistic criteria. When thinking of others, people adopt an abstract frame-of-mind, which helps generate a big-picture criterion (e.g., "What might the other person like more?") and hence makes an apples-to-oranges choice much easier. But for apples-to-apples comparisons, thinking abstractly makes the choice more difficult since a high-level criterion does not help distinguish between options that share the same features. It may be difficult to say which chess set would be more enjoyable, for example, but it should be easier to tell which is made of higher quality wood.

This reversal happens because choice difficulty is dependent on the criterion used to reach a decision. When choosing between products that share the same features such as size or color, a concrete criterion (e.g., picking the biggest size or the brightest color) is best. However, when alternatives do not share common features it is easier (and oftentimes necessary) to reach a decision by focusing on big-picture criteria (e.g., how much enjoyment will be derived from a particular option).

What This Means for Agents

Real estate professionals play a significant role in helping consumers traverse an increasingly difficult decision-making process. Understanding how to help a client make a decision can make a marked difference in his or her home-buying experience. If properly understood, the study results can help real estate professionals make the decision-making process easier, more enjoyable, and ultimately, more satisfying - which can drive repeat business, positive word-of-mouth, and referral opportunities.

One key insight for the real estate industry is this: since decision difficulty is not a stable property of a choice set, real estate professionals have an important opportunity to promote customer satisfaction and ease choice difficulty by guiding prospective buyers into an ideal state-of-mind throughout the real estate transaction.

This can be achieved by cueing specific criteria in the comparative analysis between prospective homes, creating value for the client and maximizing his satisfaction through the buying process. The challenge, though, is to elicit the right criteria at the right time:

- When helping clients decide between home options that share the same features (apples-to-apples), focus more on concrete criteria. Thinking abstractly about such options can actually make a choice more difficult. It is hard to say definitively which of three potential homes will bring a family more joy, for example; however, it will be clear which home is closest to work, has the highest-end kitchen, and has the largest yard. Low-level, feature-based criteria can help a consumer arrive at a clear preference when considering comparable alternatives.

- As the options become less and less similar, shifting to high-level abstract comparisons may reduce difficulty. Concrete feature-based comparisons, such as size of the pool or the yard can help a client navigate between homes that share those features but not between homes that do not. For example, choosing based on the size of the pool is irrelevant when one house has a pool and the other does not. In such cases, an agent should encourage a homebuyer to think about an abstract criterion, such as the potential for family enjoyment.

- Manage your client's state-of mind to avoid a no-choice option. While this research employed a forced-choice context, there are many instances - like in real estate - when consumers have the option of not choosing any of the options provided. This may not only be a waste of an agent's time and effort but may also result in regret for the consumer. Managing the client's state-of-mind by positively influencing the difficulty of his choice can increase agent sales and client satisfaction - a win-win.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

References

Bettman, James, and Mita Sujan (1987), "Effects of Framing on Evaluation of Comparable and Noncomparable Alternatives by Expert and Novice Consumers," Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 141-54.

Cho, Eunice Kim, Uzma Khan, and Ravi Dhar (2013), "Comparing Apples-to-Apples or Apples-to-Oranges: The Role of Mental Representation in Choice Difficulty," Journal of Consumer Research, 50(4), 505-16.

Iyengar, Sheena, and Mark R. Lepper (2000), "When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing?" Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995-1006.

Johnson, Michael (1984), "Consumer Choice Strategies for Comparing Non-comparable Alternatives," Journal of Consumer Research, 11(3), 741-53.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

About the Authors

Eunice Kim Cho, PhD

Assistant Professor of Marketing

Pennsylvania State University, Smeal College of Business

Professor Eunice Kim (PhD - Yale University) is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at the Pennsylvania State University. Professor Kim conducts research in the area of consumer behavior. Her current research interests are in the effects of goals, mindsets, and emotions on consumer decision making and self-regulation. Her research has been published in the Journal of Consumer Research and the Journal of Marketing Research.

Uzma Khan, PhD

Associate Professor of Marketing

Stanford University, Graduate School of Business

Uzma Khan (PhD - Yale University) is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the Graduate School of Business, Stanford University. She teaches MBA and PhD level courses on Strategic Marketing, Services Management and Consumer Behavior. Professor Khan has consulted for clients in Airline, Education and High-tech industries. Her research has won several awards including the prestigious American Marketing Association's John A. Howard Dissertation award, and the SCP-SHETH Doctoral Dissertation Award. In 2011 she was recognized by the Marketing Science Institute as a likely leader of the next generation of marketing academics.

Ravi Dhar, PhD

George Rogers Clark Professor of Management and Marketing

Yale University, School of Management

Ravi Dhar is the George Rogers Clark Professor of Management and Marketing and director of the Center for Customer Insights at the Yale School of Management. He also has an affiliated appointment as professor of psychology in the Department of Psychology, Yale University. He is an expert in consumer behavior and branding, marketing management, and marketing strategy and a leader in bringing psychological insights to the study of consumer decision-making. His research focuses on using psychological principles, such as limited self-control and cognitive limitations in processing information, to investigate fundamental aspects about the formation of consumer preferences and goals in order to understand consumer behavior in the marketplace.